When the Bough Breaks: Issues: Laws & Legislation

"Ask a man what his main concern is when he gets into prison, and he'll say getting out. Ask a woman, She doesn't say her freedom, she doesn't say getting out, she doesn't say anything else, she'll say her children. She's worried about her children." - Susie, an incarcerated mother.

Incarcerated Mothers

The female prison population has exploded in the past two decades, mainly due to mandatory-sentencing laws for drug offenses. Three times the number of women have been put behind bars in the last ten years, over 75 percent of whom have children[1]. Nationally, most of these inmates are young, unmarried women of color with few job skills and significant substance abuse problems, often incarcerated on drug convictions[2]. Yet when a mother is arrested, there is no specific public policy nor routine process to coordinate what happens to the children, even immediately after childbirth. Many women in prison claim that separation from their children is the most difficult part of their punishment.

Six percent of women are pregnant when they enter prison[3], yet most states make no special arrangements for the care of newborns. Pregnant inmates are often required to be shackled while giving birth, and after delivery, mothers and babies are sometimes separated within hours. The infant is then sent to live with a family member or is placed in the foster care system.

What About the Children?

Extended families usually assume childcare responsibilities, though many states do not recognize family relations as legitimate foster care, and deny them financial support and social services [4]. Ten percent of children with mothers in prison are sent to foster homes, while the majority of children live with grandparents [5].

The Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997 will doubtless send even more children into foster care in the future, as it allows courts to terminate parental rights if a child is in foster care for 15 months out of any 22-month period.

Three characteristics distinguish children of incarcerated parents from their peers: 1. inadequate quality of care, mainly due to poverty; 2. lack of family support; and 3. enduring childhood trauma [6].

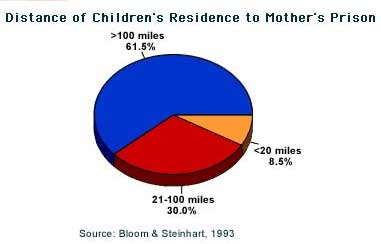

Studies show that kids with incarcerated mothers are more likely to wet their beds, do poorly in school and refuse to eat [7]. Children with mothers in prison often experience financial hardship, the shame and social stigma that prison carries, loss of emotional support and fear for their mother's safety [8] . The effect on society is equally chilling: children with imprisoned parents are at increased risk for poor academic treatment, truancy, dropping out of school, gang involvement, early pregnancy, drug abuse and delinquency [9]. These at-risk youngsters are most often overlooked by mainstream children's advocates. Unfortunately, prisons are most often located in remote rural areas and are inaccessible to families without cars. Also, because there are fewer prison facilities for women, an incarcerated woman is usually much further away from her home and is therefore much harder to visit [10], making the separation even more agonizing for both parent and child.

Too little

attention has been paid to the plights of children with incarcerated

parents and therefore too little is known about how to assist them.

There is no procedure or policy established to inquire about dependent

children when a mother is arrested. If a child is persistently truant

in school, there is no protocol to consider the disruption that

maternal incarceration causes at home, and if a child is in the

care of family services, too little about the child's emotional

history is explored before the child is placed in foster care. In

other words, there is a gap in policy and in routine communication

between the public agencies established to protect all innocent

children.

Pioneering Programs

Fortunately, some states are beginning to acknowledge the importance of mother-child relationships by introducing pioneering programs.

In a few cities in the United States, the Girl Scouts Beyond Bars program brings mothers and daughters together two Saturdays each month in prison or jail. Mothers spend supervised time working on troop projects with their daughters and discuss issues such as avoiding drug abuse, coping with family crises and preventing teenage pregnancy.

Another program is Family Foundations, a community-based residential drug treatment program based in Santa Fe Springs, California, where female inmates live in a converted school building with their children up to the age of six.

The Mothers With Infants Together (MINT) program allows eligible pregnant offenders to reside in a community-based program for two months prior to delivery and three months after delivery, empowering women to participate in prenatal and postnatal programs on childbirth, parenting and family support skills programs.

The Mothers and Children Together program in St. Louis provides cost-free bus rides to prison four times a year for families without transportation. They also organize former inmates and volunteers to lobby towards the improvement of visiting opportunities at the state capital, and hold support groups for recently released mothers, children and caregivers in St. Louis.

New York's Bedford Hills Correctional Facility opened the nation's first nursery prison 100 years ago, and continues to offer a range of services to inmates and their children, including a well-equipped playroom that is open 365 days a year. Run by Catholic Charities, it is designed to teach women parenting and life skills through classes and by allowing them to receive visits from their children as often as possible in a nurturing atmosphere. Only 10 percent of women who successfully completed the program returned to prison, in contrast to 52 percent of inmates overall [11].

Statistics

Mothers

In Prison

-

Two of every three women in prison are mothers of young children. (U.S. Department of Justice) ¥ Half of the 250,000 children whose mothers are incarcerated never get to visit their mother while she's away. (U.S. Department of Justice)

-

Nearly half of female inmates are non-violent offenders. (Bureau of Justice Statistics)

-

Incarcerated women are overwhelmingly poor. The majority of women prisoners (53 percent) and women in jail (74 percent) were unemployed prior to incarceration. (National Women's Law Center)

-

Over 40 percent of women report that they were victims of abuse at least once before their incarceration. (U.S. Department of Justice)

-

47 percent of female inmates (compared to 37 percent of male inmates) had at least one immediate family member who had been incarcerated. (U.S. Department of Justice)

-

Thirty-six percent of the women interviewed had been separated from at least one child during the child's first three years of life. This correlates with the common finding that women who give birth while incarcerated often have to relinquish care of their child to a relative, friend or foster parent within 24 hours of the child's birth. (National Council on Crime and Delinquency)

Children With Incarcerated Mothers

-

A 1993 study found that when children were placed with caregivers during their mother's incarceration, 40 percent of the male teenagers had some involvement with the juvenile justice system; 60 percent of female teenagers were or had been pregnant; and a third of all children experienced severe school-related problems. (American Correctional Association)

-

Over 60 percent of mothers in prison are incarcerated more than 100 miles from their children, making visitation difficult, financially prohibitive and often impossible. (National Council on Crime and Delinquency)

-

Nationally, foster care for a prisoner's child costs between $15,000 and $20,000 per year, adding to the cost of incarcerating their caregivers. (City Limits, 1997)

-

Children with inmate mothers are six times more likely than their peers to end up behind bars. (Center for Children of Incarcerated Parents)

-

Since 1990, the number of children with a mother in prison has nearly doubled. (U.S. Dept of Justice Bureau of Justice statistics)

Footnotes :